Energy Management for the Time-Poor: A Survival Guide for High-Constraint Lives

A few weeks ago, I visited two friends in the Netherlands. They’re both senior software engineers, they just had their second baby, and right now, they’re surviving on less than four hours of sleep a night. Honestly? They looked smart, kind, committed – and completely wrecked.

Over dinner, they told me a story I hear all the time from high-skill workers and new parents: they know AI is moving fast, they know their industry is changing, and they’d love to keep learning – but they have zero bandwidth left. Every single hour is claimed by the baby, the toddler, the sprint board, the pager, or the laundry pile.

When I got home, I tried to find some energy strategies for them. But pretty quickly, I realized most popular productivity advice quietly assumes you actually control your time. You know the drill: “deep work blocks,” “30-minute meditations,” “45-minute runs,” “eight hours of perfect sleep.” My friends – and probably many of you – are basically excluded from that conversation by design.

So, I dug into the research on sleep, stress physiology, and high-constraint working lives. I also talked to real people living this reality. This article is the practical version of what I found.

TL;DR · Key takeaways

- If your life is tightly scheduled by work, shifts, and caregiving, your problem isn’t willpower – it’s a chronically over-taxed nervous system.

- Before blaming yourself, check for hidden biological causes of fatigue (vitamin D, B12, iron stores, thyroid function).

- Three things keep you exhausted: unfinished stress cycles, prefrontal overload, and mistimed rhythms.

- Recovery for the time-poor happens in layers: micro-recovery for your body, “third space” rituals for your mind, and gentler ways to handle distraction.

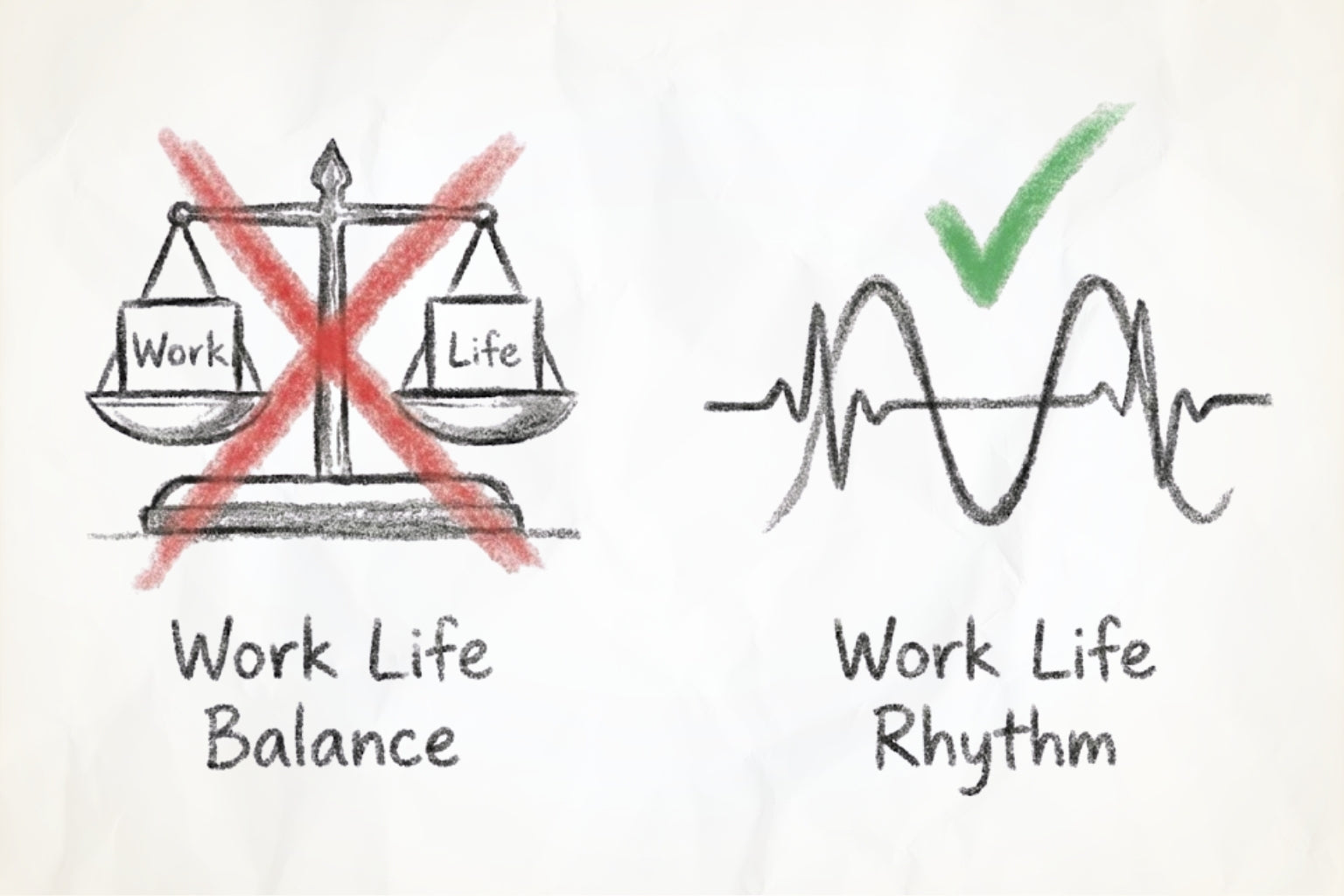

- You don’t need “work–life balance”; you need a work–life rhythm your actual biology can sustain.

Who is this guide for?

In this article, I use the term high-constraint person to describe folks whose main struggle isn’t a lack of discipline, but a lack of autonomous time.

If any of this sounds like your life, you’re probably in this group:

- You wake up tired, go to bed even more tired, and still lie awake scrolling.

- Your sleep gets smashed by babies, night shifts, on-call duty, or late-night customer issues.

- You’re constantly running a mental spreadsheet of appointments, deadlines, and family logistics.

- When you finally sit down in the evening, you’re too wired to rest but too drained to do anything real.

For high-constraint people, energy management isn’t a fun self-improvement hobby. It’s survival. The goal here isn’t to turn you into a productivity machine, but to give your nervous system a fighting chance inside the life you actually have.

Why am I this tired, and why doesn’t normal “rest” help?

What hidden health issues should I check first?

A surprising number of “burnout” and “mild depression” cases turn out to be something more basic: specific nutrient depletion or hormone issues that never got tested properly. Before you overhaul your whole life or question your character, it’s worth ruling out some common physical causes that silently drain your battery:

- Vitamin D (25-OH): helps regulate your sleep–wake rhythm and energy levels. Deficiency often feels like muscle aches and everything just feeling “harder” than it should.

- Vitamin B12: keeps your nerves insulated and is key for making dopamine and serotonin. Low B12 feels like brain fog mixed with zero drive.

- Ferritin (iron stores): helps make dopamine; hidden iron deficiency can create a “chemical lack of motivation” even if your haemoglobin looks normal.

- Thyroid function (TSH, FT3, FT4, antibodies): chronic stress and high cortisol can push you into a “subclinical” state – technically normal labs, but you feel cold and exhausted. (Ask your doctor which markers were actually tested.)

Tool · Hidden Fatigue Checklist

I made a one-page checklist you can print or save to your phone for your next GP visit. It lists the key tests, why they matter, and target ranges based on current research.

This checklist is for discussion with your doctor. It does not replace medical advice.

What biological mechanisms keep me exhausted?

1. Unfinished stress cycles and chronic overload

Our stress response was designed for short emergencies: see threat, react, run/fight, recover. In a high-constraint life, the threats never stop coming: work crisis A → childcare chaos B → sleep disruption C. The stress cycle never actually closes, so your nervous system stays stuck in “on” mode.

This means your evening cortisol never drops enough. Even if you technically “sleep,” it’s shallow and fragmented. You wake up feeling like your brain never really went offline for repairs.

2. Prefrontal overload and a shrinking energy budget

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) – the part of your brain that handles planning, impulse control, and decisions – is super energy-hungry. For high-constraint folks, mental load (remembering schedules, monitoring kids, tracking shifting priorities) constantly drains fuel from that region.

This is why, after a certain point in the day, you physically can’t “just say no” to one more episode or one more scroll: the neural hardware you need for self-control has gone offline. What feels like a moral failing is often just a brain that’s run out of gas.

3. Ignored rhythms and mistimed interventions

Besides the 24-hour circadian rhythm, our brains run on shorter ultradian cycles of about 90–120 minutes – a wave of focus followed by a dip where your system demands a reset. High-constraint people usually bulldoze through that dip with caffeine, sugar, or panic.

The result? “Fake energy” propped up by stress hormones. Over time, your body forgets how to down-shift on its own. You end up tired all day, wired at night, and unable to sleep without a screen in your face.

How can I start recovering if I can’t add more rest?

Once you’ve ruled out the obvious health stuff, the question is: What can I actually do with the scraps of time and energy I have? In this framework, recovery happens in three layers:

- Physical recovery – what you do with your body and sleep.

- Psychological recovery – how you switch roles and unload your mind.

- Dopamine and distraction management – dealing with addictive apps when you’re depleted.

How can I support my body on fragmented sleep?

Micro-recovery when real sleep isn’t happening

If you’re a new parent, night-shift nurse, junior doctor, warehouse worker, or on 24/7 pager duty, “sleep 8 hours” isn’t advice – it’s a fantasy. The priority has to shift from optimizing sleep to preserving wakefulness and managing debt.

Non-Sleep Deep Rest (NSDR) – think Yoga Nidra, guided body scans, or self-hypnosis – helps move your brain from high-stress states into a zone between waking and sleeping where you can actually replenish some energy. Studies on yoga nidra show it reduces stress and improves sleep quality even for insomniacs. Even short sessions can be a lifesaver in those 10–20 minute gaps between responsibilities.

How do I anchor my rhythm when my schedule is chaos?

For shift workers and new parents, the goal isn’t a perfect 11 p.m. bedtime. It’s preventing your body clock from completely losing the plot:

- Anchor sleep: try to protect a core block of roughly four hours that overlaps on most days (like 2–6 a.m.). That block becomes the “anchor” your system holds onto.

- Split sleep: if 7–9 straight hours are impossible, think in terms of 4+3 or 5+3 hours. Split sleep can preserve your brain function almost as well as continuous sleep, as long as the total time adds up.

- Tactical light: block light on your way home from night shifts (blue-blocking glasses work) and get bright light as soon as you decide “this is my morning,” even if that’s at 3 p.m.

How do I know if I have central vs. peripheral fatigue?

One big mistake in standard advice is treating all fatigue the same. I distinguish between peripheral fatigue (muscles, joints, body) and central fatigue (brain, focus, emotional labor). They need different fixes:

- If you do physical or manual work all day, “active recovery runs” might just make you feel worse. You need decompression: hanging from a bar, legs-up-the-wall, contrast showers, massage, or just gentle stretching.

- If you sit, think, and care all day, your body is under-used but your nerves are fried. You need transition walks, panoramic vision, physiological sighs, and NSDR to reboot the system.

Tool · 5–20 Minute Micro-Recovery Menu

To make this actionable, I turned these protocols into a one-page “menu”. Check how much time you have (5, 10, or 15–20 mins), then pick one option for a fried brain or one for a wrecked body.

How do I recover mentally when work and home blur together?

In high-constraint lives, the hardest part isn’t just the workload—it’s the lack of boundaries. Work stress bleeds into home; home chaos bleeds back into work. You get home physically, but your head is still on Slack or in the ward.

Research shows that recovery quality depends less on how long you rest and more on how completely your mind stops replaying work problems. The “third space” is that tiny gap between roles – the car after parking, the walk from the bus stop, the moment on the bench outside – where you can run a deliberate transition ritual.

Think of this as a 3–5 minute bridge: closing the open loops from your last block, calming your nervous system, and choosing how you want to show up for whatever’s next.

Tool · Third Space Card

I turned the Reflect–Rest–Reset protocol into a small card you can keep in your car, hallway, or on your phone. It gives you a quick script to switch from “worker mode” to “human / parent / partner mode.”

Beyond the third space, psychological recovery for high-constraint people also includes:

- Compassion over pure empathy: for frontline workers, shifting from “I feel your pain” (which burns us out) to “I care about you; what can I realistically do?” uses different brain networks and is way less draining.

- Cognitive off-loading: building an “external brain” like a low-tech family command center so your walls, not your working memory, hold the schedule.

How can I handle distraction and revenge bedtime scrolling?

When I interviewed people for this, the #1 struggle wasn’t starting work—it was stopping doom-scrolling and late-night binging. Most high-constraint people know revenge bedtime procrastination hurts them; they just don’t see any other way to feel like they own their time.

In this framework, late-night scrolling isn’t a character flaw. It’s your exhausted brain trying to reclaim some agency and dopamine after a day where every minute belonged to someone else. To change it, we work with that need instead of shaming it.

- Environment design (“outsourcing willpower”): using phone lock-boxes, grayscale mode, or leaving devices in another room adds just enough friction so you don’t have to fight yourself at 1 a.m.

- Low-dopamine mornings: protecting the first 60–90 minutes of your day from screens keeps your baseline dopamine low enough that normal life feels bearable instead of boring.

- Compassion-based scripts and “urge surfing”: instead of “I’m useless, I failed again,” try: “I’m staying up because I desperately want time that feels like mine. That’s valid. But for tomorrow’s sake, I’m logging off.” Then ride the craving wave for three minutes—notice how it rises and falls without acting on it.

What is a simple 3-step plan I can start today?

If this feels like a lot, here is a minimal, science-backed plan for the next seven days.

- Do one health check step. Book that GP appointment. Bring the checklist, or look up your old labs to see what you missed.

- Claim one micro-recovery slot per day. Use the menu and pick just one protocol that fits your time and fatigue type.

- Add one third-space ritual. Before you walk into your home (or your next role), pause for 3–5 minutes and run the script: Reflect, Rest, Reset.

FAQ · Common questions about high-constraint energy management

How do I know if I’m really high-constraint or just bad at planning?

If most of your waking hours are dictated by other people’s needs – patients, kids, customers, bosses – and you can’t just shuffle things around to make a four-hour deep work block, you’re dealing with constraints, not poor planning. This guide is for you.

Can micro-recovery replace real sleep?

No. Nothing replaces actual sleep. Think of micro-recovery and NSDR as damage control: they help your nervous system survive seasons when full sleep isn’t happening, and they can improve the quality of the sleep you do get, but they aren’t a long-term substitute.

What if my labs are “normal” but I still feel awful?

First, ask your doctor where you fall in the reference range—sometimes “normal” isn’t “optimal.” Second, remember that lifestyle, mental load, and environment can exhaust a perfectly healthy body. If that’s the case, the non-medical tools in this article are even more critical.

Is it worth trying if I only have 5–10 minutes a day?

Yes. For a fried nervous system, even a few minutes of deliberate down-regulation can make a real difference over time. Think of it as planting tiny anchors for your brain instead of waiting for a perfect free weekend that’s never coming.

When should I talk to a professional?

If your fatigue gets suddenly worse, if you have chest pain, shortness of breath, or other alarming symptoms, or if you feel persistently low for more than two weeks, please talk to a medical or mental health professional ASAP.

What are some key facts from the research?

- Studies on yoga nidra and similar practices show they can reduce stress and improve sleep quality for adults with high stress or insomnia.

- Vitamin D deficiency is linked to fatigue, and correcting it has been shown to improve energy levels in deficient adults.

- Iron deficiency without anaemia is common (especially in women) and is linked to tiredness, brain fog, and lower physical performance.

- Being able to psychologically detach from work during off-hours predicts better mental health and lower burnout, regardless of how many hours you work.

- Excessive phone use hurts sleep and mental health; changing your environment (nudges) works better than willpower to cut down usage.

What does “work–life rhythm” look like in practice?

Classic “work–life balance” suggests you can balance two heavy weights perfectly. For high-constraint people, that metaphor isn’t just unhelpful—it’s cruel. There is no clean split between “work” and “life”; there’s only a messy, overlapping rhythm.

A more honest goal is to design a work–life rhythm that respects: your body’s ultradian waves (90-minute pulses of focus and rest), your circadian anchors (sleep and light patterns you can actually protect), and the hard limits of your brain under chronic load.

The tools here – the Checklist, the Menu, the Card – aren’t magic bullets. They are small, high-leverage levers for people with almost no spare capacity who still want to show up as a decent colleague, parent, partner, or just... themselves.

You don’t have to fix your whole life this week. Start by claiming one 5-minute break, one four-hour anchor block, or one transition ritual. That’s how a new rhythm begins.

This article is based on a review of recent neuroscience, sleep, and stress research, plus interviews with high-constraint workers and parents. It is for education, not medical diagnosis. Please work with your healthcare pros when making changes to meds, supplements, or schedules.

Further reading & sources

- Yoga nidra & NSDR: Datta K. et al. “Yoga nidra practice shows improvement in sleep in patients with chronic insomnia: a randomized controlled trial,” National Medical Journal of India, 2021, and related studies.

- Vitamin D and fatigue: Nowak A. et al. “Effect of vitamin D3 on self-perceived fatigue,” Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, plus later reviews.

- Iron deficiency without anaemia: Soppi E. “Iron deficiency without anemia – common, important, and underdiagnosed,” Clinical Case Reports and Reviews, 2018.

- Work recovery & detachment: Sonnentag S. and colleagues on psychological detachment and recovery experiences.

- Digital overuse & nudging: Research on smartphone overuse, sleep, and “active nudging” designs for digital well-being.